A new report by SkyNRG has found the U.S. is not on track to meet its 2030 sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) goals.

The Netherlands-based SAF producer recently published its 2023 Sustainable Aviation Fuel Market Outlook, which covers trends in the SAF markets in the U.S., U.K. and European Union based on an analysis of announced and ongoing SAF projects.

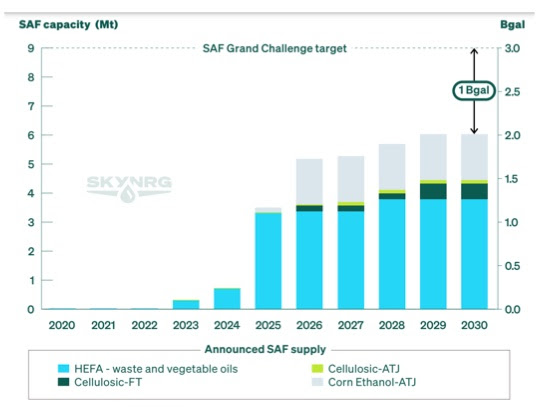

1 billion missing gallons

The analysts found that if every announced plan to produce SAFs succeeded, companies such as Honeywell, Neste and SkyNRG would produce about 2 billion gallons of SAF annually by 2030. Unfortunately, that’s about 1 billion gallons short of the federal government’s SAF Grand Challenge goal of 3 billion gallons of SAF produced annually in 2030. In addition, the report determined it would be challenging to reach the secondary goal of all airlines using only SAF by 2050. Using a pre-COVID air travel base, 100 percent SAF deployment would amount to 27 billion gallons annually.

What will it cost?

The U.S. will require some 250 new SAF refineries to reach its 2050 production goal, according to the report. That would cost an estimated $400 billion in cumulative capital expenditure investments to supply all U.S. airlines with 27 billion gallons of sustainable fuel annually. That amounts to an average annual capital cost combined among airlines and SAF producers of $16 billion between 2025 and 2050. The report authors note, “These assumptions are considered to be on the optimistic side, which tells us that already satisfying pre-Covid jet fuel demand with 100% SAF will be a major challenge for the US.”

There’s another caveat: As I noted earlier, the 27 billion gallon goal for U.S. airlines represents the demand for jet fuel pre-COVID, and so far air travel demand has not fully recovered from the pandemic. However, if air travel exceeds pre-COVID levels by 2050, the report finds it unlikely that the U.S. will reach 100 percent SAF deployment.

What can the government do?

The Inflation Reduction Act provides significant investments in research and development, as well as incentives for producing SAF. Currently the Treasury Department is drafting guidance for claiming tax credits for SAF production. The Sustainable Aviation Fuel Blender’s Tax Credit (BTC) will be available between 2022 and 2025 and the Clean Fuel Production Tax Credit from 2022 to 2027.

At the state level, Illinois, Washington and California passed SAF incentives that can add on to federal tax credits, which will help grow SAF industries locally.

But the authors note that these incentives do not last long enough. And these programs will likely only benefit SAF projects that already exist. If this is the case, federal and state governments would need to establish long-term programs to incentivize building out the SAF market.

Do we have enough crops?

Yes — but mostly no.

According to the report, future demand for renewable diesel will strain the waste and vegetable markets beyond their current capacity. This is not good news considering available waste and vegetable oils in the U.S. were fully consumed in 2022, the report found. To meet the growing demand for SAFs, U.S. manufacturers will need to import feedstocks, which will drive up prices.

But there is some good news. Much of the renewable diesel currently using all the waste and vegetable oil is used to power road transport vehicles. So, if the EV transition continues, and if governments shift their incentive programs from biodiesel to SAFs, then the crops and waste used for road fuels will be freed up for jet fuels.

The U.S. could also make up for the lack of available feedstocks by producing corn-based ethanol or by shifting food supply production, but the latter would have serious consequences for trade and food security.

That said, there are a host of environmental drawbacks that come with biofuels. For instance, land-use change, the practice that includes converting forests or wildlands to farming, causes carbon emissions from deforestation and other vegetation removal. Additionally, modern farming reduces biodiversity, and runoff from farmland can pollute waterways.

Bottom line

The aviation industry is “hard to decarbonize” for a reason. Unlike the U.S., the EU has employed mandates to grow its sustainable fuel supply. It remains to be seen if that approach is better than the short-term subsidies currently offered in the U.S. Overall, airlines, SAF manufacturers and the government need a serious, long-term investing approach to reduce the cost of transitioning to SAF.

And, keeping biofuels truly sustainable will require regulatory oversight that will mitigate or prevent carbon dioxide emissions from land-use changes. Truly sustainable feedstock will need to promote biodiversity without running afoul of our food and water supply.

Ultimately, even in the best case scenario, flying less and paying more to do it will be the price of a truly sustainable aviation industry. Customers may have become accustomed to relatively cheap air travel, but everyone will pay for the externalized costs one day, either through climate change catastrophe or a more expensive ticket to ride.